They Remembered the Lost Women of the Manhattan Project So That We Wouldn't Forget

- Av

- Episod

- 43

- Publicerad

- 31 aug. 2023

- Förlag

- 0 Recensioner

- 0

- Episod

- 43 of 95

- Längd

- 11min

- Språk

- Engelska

- Format

- Kategori

- Fakta

In the early 1990s, two physicists, Ruth Howes and Caroline Herzenberg, began looking into a question that had aroused their curiosity: Just who were the female scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project?

Nearly ten years and hundreds of interviews later, they documented hundreds of women across a broad spectrum of scientific fields — physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics — who played crucial roles in the top-secret race to build a nuclear weapon that would end World War II.

Since the film Oppenheimer came out earlier this summer, Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project has enjoyed a revival of sorts as new attention is paid to the women for whom recognition is long overdue.

They Remembered the Lost Women of the Manhattan Project So That We Wouldn't Forget

- Av

- Episod

- 43

- Publicerad

- 31 aug. 2023

- Förlag

- 0 Recensioner

- 0

- Episod

- 43 of 95

- Längd

- 11min

- Språk

- Engelska

- Format

- Kategori

- Fakta

In the early 1990s, two physicists, Ruth Howes and Caroline Herzenberg, began looking into a question that had aroused their curiosity: Just who were the female scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project?

Nearly ten years and hundreds of interviews later, they documented hundreds of women across a broad spectrum of scientific fields — physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics — who played crucial roles in the top-secret race to build a nuclear weapon that would end World War II.

Since the film Oppenheimer came out earlier this summer, Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project has enjoyed a revival of sorts as new attention is paid to the women for whom recognition is long overdue.

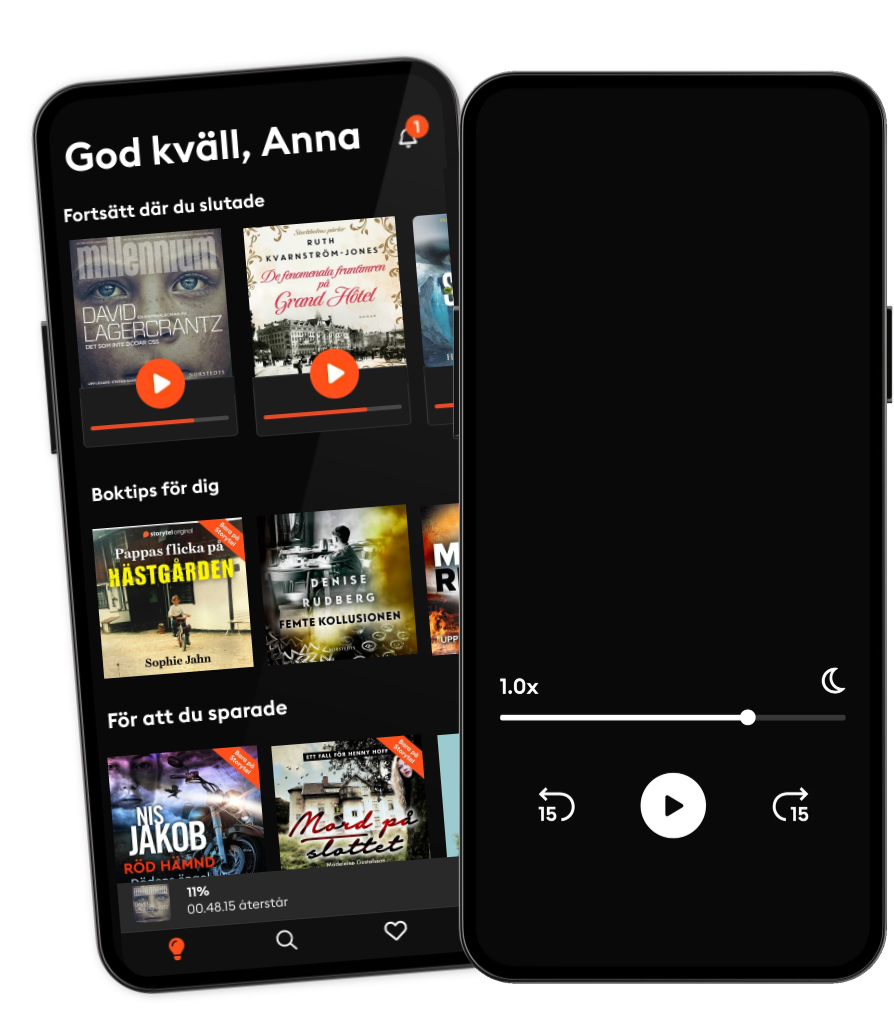

Lyssna när som helst, var som helst

Kliv in i en oändlig värld av stories

- 1 miljon stories

- Hundratals nya stories varje vecka

- Få tillgång till exklusivt innehåll

- Avsluta när du vill

Andra podcasts som du kanske gillar...

- Still Online - La nostra eredità digitaleBeatrice Petrella

- This American LifeThis American Life

- Dr. Death | S1: Dr. DuntschWondery

- The Book ReviewThe New York Times

- True StoryMartin Hylander

- Anupama Chopra ReviewsFilm Companion

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- Do I Like It?The Quint

- The SoapyRao ShowSundeep Rao

- Anden omgangLouise Kjølsen

- Still Online - La nostra eredità digitaleBeatrice Petrella

- This American LifeThis American Life

- Dr. Death | S1: Dr. DuntschWondery

- The Book ReviewThe New York Times

- True StoryMartin Hylander

- Anupama Chopra ReviewsFilm Companion

- FC PopCornFilm Companion

- Do I Like It?The Quint

- The SoapyRao ShowSundeep Rao

- Anden omgangLouise Kjølsen

Svenska

Sverige