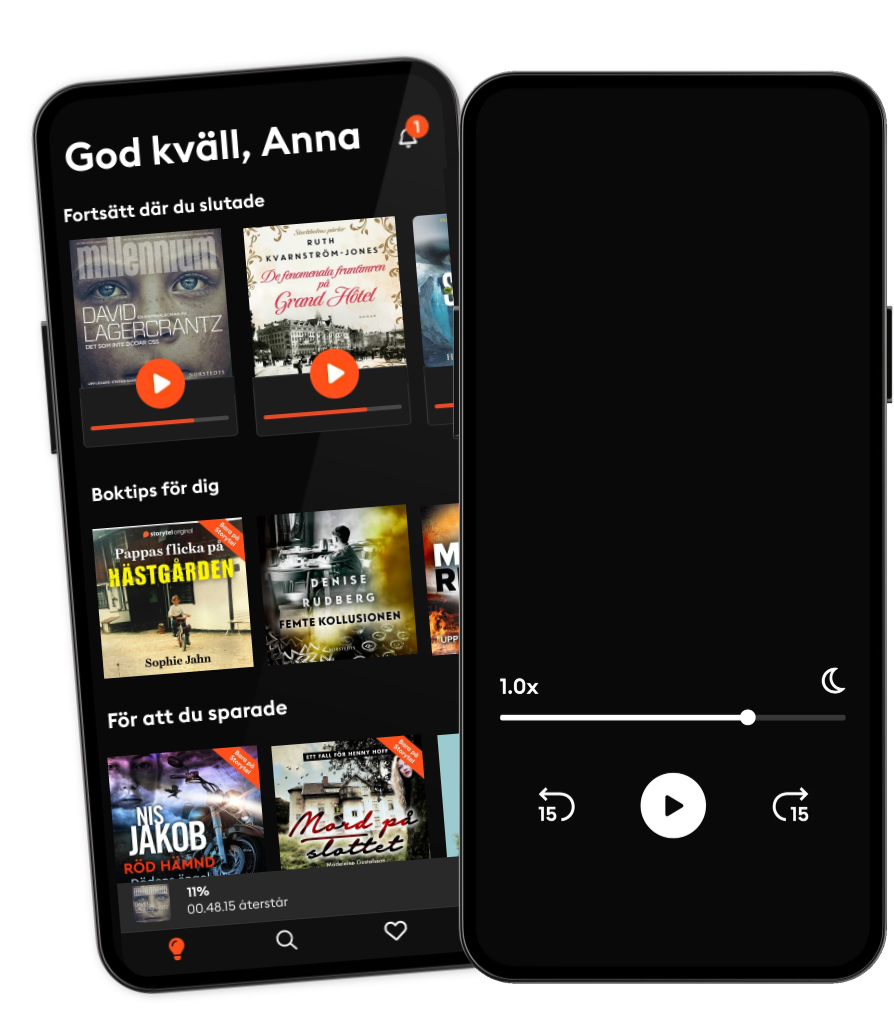

Lyssna när som helst, var som helst

Kliv in i en oändlig värld av stories

- 1 miljon stories

- Hundratals nya stories varje vecka

- Få tillgång till exklusivt innehåll

- Avsluta när du vill

Creating Your Children's Book

How to Write That Children's Book You've Always Wanted

Have you ever thought to go ahead, sit down, and write that story which keeps coming into your mind? That one that's "childish" or "juvenile"? Maybe you already "see" the pictures which should go with it?

Maybe you’re one of those lucky writers whose head is bursting with ideas. Or perhaps you have one idea that’s been nagging you for weeks, always at the edge of your thoughts. Either way, you’re itching to begin writing…

A lot of writers, especially when they’re beginners, get ideas for fiction from their own lives. This can be useful for several reasons: you’re emotionally invested in the topic, you can relate directly to the main character, and if the situation actually happened to you, you’re less likely to be unconsciously basing the story on a book you’ve read…

When writers stick too closely to what really happened they fail to develop the elements necessary for a good story: a believable main character who is faced with a problem or conflict, mounting tension as that character tries to solve her problem and experiences setbacks, and a tension-filled climax followed by a resolution that’s satisfying to the character and the reader. If your main character is really your son, you might not want to get him in trouble or throw rocks in his path. But you have to. It’s the only way you’ll create a story that will keep readers hooked and wondering how it will end.

However you get your idea, focus first on whether it’s a plot or a theme. Many times, an initial idea is really the underlying meaning of the story, what the author wants to convey to the reader.

Themes should be universal in their appeal– such as friendship, appreciating one’s own strengths, not judging others too quickly. Then play around with the sequence of events until you develop a plot (what actually happens in the book) that makes this theme clear to the reader.

And remember: if you’re using a childhood incident as the foundation of your story, tell it from your childhood viewpoint, not how it feels to you now as an adult…

(From Chapter 2)

Have you ever thought to go ahead, sit down, and write that story which keeps coming into your mind? That one that's "childish" or "juvenile"? Maybe you already "see" the pictures which should go with it?

Maybe you’re one of those lucky writers whose head is bursting with ideas. Or perhaps you have one idea that’s been nagging you for weeks, always at the edge of your thoughts.

Either way, you’re itching to begin writing…

A lot of writers, especially when they’re beginners, get ideas for fiction from their own lives. This can be useful for several reasons: you’re emotionally invested in the topic, you can relate directly to the main character, and if the situation actually happened to you, you’re less likely to be unconsciously basing the story on a book you’ve read…

When writers stick too closely to what really happened they fail to develop the elements necessary for a good story: a believable main character who is faced with a problem or conflict, mounting tension as that character tries to solve her problem and experiences setbacks, and a tension- filled climax followed by a resolution that’s satisfying to the character and the reader.

If your main character is really your son, you might not want to get him in trouble or throw rocks in his path. But you have to.

It’s the only way you’ll create a story that will keep readers hooked and wondering how it will end.

However you get your idea, focus first on whether it’s a plot or a theme. Many times, an initial idea is really the underlying meaning of the story, what the author wants to convey to the reader.

Themes should be universal in their appeal– such as friendship, appreciating one’s own strengths, not judging others too quickly. Then play around with the sequence of events until you develop a plot (what actually happens in the book) that makes this theme clear to the reader.

And remember; if you’re using a childhood incident as the foundation of your story, tell it from your childhood viewpoint, not how it feels to you now as an adult…

(From Chapter 2)

How to Write That Children's Book You've Always Wanted

Have you ever thought to go ahead, sit down, and write that story which keeps coming into your mind? That one that's "childish" or "juvenile"? Maybe you already "see" the pictures which should go with it?

Maybe you’re one of those lucky writers whose head is bursting with ideas. Or perhaps you have one idea that’s been nagging you for weeks, always at the edge of your thoughts. Either way, you’re itching to begin writing…

A lot of writers, especially when they’re beginners, get ideas for fiction from their own lives. This can be useful for several reasons: you’re emotionally invested in the topic, you can relate directly to the main character, and if the situation actually happened to you, you’re less likely to be unconsciously basing the story on a book you’ve read…

When writers stick too closely to what really happened they fail to develop the elements necessary for a good story: a believable main character who is faced with a problem or conflict, mounting tension as that character tries to solve her problem and experiences setbacks, and a tension- filled climax followed by a resolution that’s satisfying to the character and the reader. If your main character is really your son, you might not want to get him in trouble or throw rocks in his path. But you have to. It’s the only way you’ll create a story that will keep readers hooked and wondering how it will end.

However you get your idea, focus first on whether it’s a plot or a theme. Many times, an initial idea is really the underlying meaning of the story, what the author wants to convey to the reader.

Themes should be universal in their appeal– such as friendship, appreciating one’s own strengths, not judging others too quickly. Then play around with the sequence of events until you develop a plot (what actually happens in the book) that makes this theme clear to the reader.

And remember; if you’re using a childhood incident as the foundation of your story, tell it from your childhood viewpoint, not how it feels to you now as an adult…

(From Chapter 2)

© 2017 Midwest Journal Press (E-bok): 9781329176737

Utgivningsdatum

E-bok: 21 augusti 2017

Taggar

Andra gillade också ...

- Let's parler Franglais! Miles Kington

- Time to Talk: What You Need to Know About Your Child's Speech and Language Development Carlyn Kolker

- 3-Minute Afrikaans: Bonus Audiobook: 400 Actions & Activities - Everyday Afrikaans for Beginners Innovative Language Learning

- Unconditional Parenting: Moving from Rewards and Punishments to Love and Reason Alfie Kohn

- Using Stories to Teach Maths Ages 4 to 7 Steve Way

- 100+ Fun Ideas for Teaching French across the Curriculum Nicolette Hannam

- Cats All Dressed Up Xist Publishing

- Power French 3 Accelerated: Learn to Quickly Speak Advanced Level French and Enjoy the Process! Mark Frobose

- Smartphone French I Intensive: Designed Specifically to Teach You French While on the Go. Learn Wherever You Are on Your Smartphone, in Your Car, At the Gym, While Traveling, Eating Out, Or Even At Home! Mark Frobose

- Power French Verbs 2: Learn to Speak Real French with Intermediate to Advanced High Frequency French Verbs! Mark Frobose

- Sömngångaren Lars Kepler

4.2

- Väninnorna på Nordiska Kompaniet Ruth Kvarnström-Jones

4.1

- Ingen Pascal Engman

4.2

- Död mans kvinna Katarina Wennstam

4.3

- Benådaren Viveca Sten

4.1

- Är det nu jag dör? Leone Milton

3.8

- Drottningen Jonas Moström

3.8

- De fenomenala fruntimren på Grand Hôtel Ruth Kvarnström-Jones

4.5

- Livor mortis Mikael Ressem

4

- De döda och de levande Anders Nilsson

4.3

- Älskade jävla unge Pernilla Pernsjö

4.5

- Älskade Betty Katarina Widholm

4.3

- Anteckningar från aftonsången Jan Guillou

3.5

- Hembiträdet Freida McFadden

4.2

- Hundra dagar i juli Emelie Schepp

4

Därför kommer du älska Storytel:

1 miljon stories

Lyssna och läs offline

Exklusiva nyheter varje vecka

Kids Mode (barnsäker miljö)

Premium

Lyssnar och läs ofta.

1 konto

100 timmar/månad

Exklusivt innehåll varje vecka

Avsluta när du vill

Obegränsad lyssning på podcasts

Unlimited

Lyssna och läs obegränsat.

1 konto

Lyssna obegränsat

Exklusivt innehåll varje vecka

Avsluta när du vill

Obegränsad lyssning på podcasts

Family

Dela stories med hela familjen.

2-6 konton

100 timmar/månad för varje konto

Exklusivt innehåll varje vecka

Avsluta när du vill

Obegränsad lyssning på podcasts

2 konton

239 kr /månadFlex

Lyssna och läs ibland – spara dina olyssnade timmar.

1 konto

20 timmar/månad

Spara upp till 100 olyssnade timmar

Exklusivt innehåll varje vecka

Avsluta när du vill

Obegränsad lyssning på podcasts

Svenska

Sverige